[Engwentro googled image]

[bertolucci image]

That is, going back to what i love most, watching films on Tuesday nights and spending my careful research on 'some contemplative films' on Friday nights. I have heard recently that Engkwentro (2009) directed by Pepe Diokno won the Orrizonti prize under New Horizons category in the recently concluded 66th Venice Film Fest. Pepe Diokno is twenty one years old. As you might recall, last year's Orrizonti Award was given to our very respected and loved, Lav Diaz with his feature Melancholia (2008). Oggs presented a careful observation of Engkwentro's style. He wrote:

"Perhaps the most glaring difference is style. While Libiran sometimes indulges in long takes (there's a particularly lovely scene where Libiran's camera follows a utilities man who is mobbed by Tondo residents who are complaining about their electricity bills), Diokno attempts to tell his story in one long take. He failed at that attempt but achieves something close. Engkwentro is composed of a couple of takes, seemingly seamlessly edited together by Miko Araneta. Diokno's camera is constantly in motion: candidly shaking as it treads the labyrinthine passageways of his makeshift slums; following the characters as they hatch their plans, negotiate, orate and fight; and document the goings-on with the efficiency of an inconspicuous voyeur." (here)Long takes, that is. It is not clear, however, if mise-en-scene staging (i.e. staging in deep space as in Welles' Citizen Kane (1941) or Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev (1969)) was Oggs's point here. If the long take was made as a cinematographic effect, obviously, because Oggs later observe that the camera was moving, it might have a different function. Let us say, the use of Jean Renoir's long take, mobile camera on La Grande Illusion (1937) functions differently as long take, steady camera of Welles in Magnifecent Ambersons. In an interview with the Inquirer Pepe Diokno clarifies this aesthetic choice saying:

"...that the 61-minute film was done with one long take. “Actually, there were 51 cuts, but we had to digitally erase the cuts and make it look seamless. We wanted to make it appear continuous, as if it was one long tracking shot.”" (here)

I think this 'volatile' use of long take, handheld camerawork can be connected with the cinematography of Wong Kar-wai and obviously related to the style that proliferated in 1960s art film cinema, the cinéma vérité. I have made a careful observation after watching Alan Clarke's 1988 film, Elephant, that:

"The object of contemplation will be lost, however, if the directors will pursue this (handheld camera) cinematic style. It can be thought that hand-held cameras may depict the theme of violence... with much accuracy because it can deploy much of the needed hastiness and immediacy of the gunner shooting a victim. It can also add a lot of psychological positioning as post-compositional effects. This style is common in art house cinemas especially in the independent waves in the 80s. Kubrick did use a handheld camera when he filmed certain scenes in The Shinning (1980)."(here)If cinéma vérité style is central to Engkwentro's camera, correct me if I am wrong, nothing is more 'cinéma vérité' than my Saturday night movie madness on Neill Blomkamp's District 9 (2009) which is still showing at SuperMart theaters this week.

District 9

District 9 is a mesh of documentary-style and special effects, and to see young audiences sitting next to me enjoying the terrifying treat amazes me. The film is a bit 'horrory' for an age of 14 or 15. I, myself, am shocked by the visuals of District 9. It has a highly developed aesthetics that deserve academic study, whatever the inconsistencies present in its form, for example, the surveillance footage style, if remember it completely, have some shot/reverse shots effects. Who could find a surveillance camera with such high cinematography???

Bertolucci and Celebrating One Year of Cinephilia

Finally, the highlight of my week, aside from Godard, is a string of films by Bernando Bertolucci which I have recently acquired namely his masterpiece, The Conformist (1970), his most controversial film that drived Pauline Kael crazy, Last Tango in Paris (1973), his Oscar winning The Last Emperor (which I purchased last month), and his recent feature The Dreamers (2003).

One can say that I am living in an auteur's world. A couple of days ago, my friend observes: "Oh! Wow! you have almost all Scorseses [he was refering to Scorsese's oeuvre which I have carefully been collecting.]." I replied: "Believe me, I don't have. You are talking of 21 features, 8 documentaries, 7 shorts. And they are not all in DVD, not that i can recall. And I don't have enough money."

This issue of collecting oeuvre of filmmakers, as in my attempt to collect all Kurosawas, Brillante Mendozas, Lav Diaz-es, Godards, Hitchcocks, Murnaus, Almodovars and Renoirs, is highly frustrating. You can't collect them all in DVDs, particullarly on a high-definition, notable, unstrangled DVD copies. I have this recent urge to unmasked all of history of film (at least the most notable) and to lay it on my table and select my top 20 best films of all time. To date, my cinephiliac wanderings have been continuing for about a year now. It started way, way back when i posted my article: "A Consuming Film Research: First Steps." published in this blog last September 10, 2008. A year and six days passed and over two hundred films and more than fifty film books, I can say that I have been successful in my undertaking to transforming myself into a film blogger, and the best thing, a film cinephile.

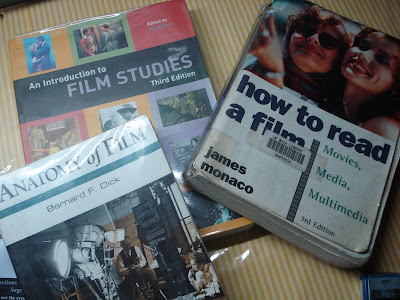

Do you remember this picture from my September 10, 2008 post?

These are my first film books that I have read in my whole life. Before I cut this post, I have long admired this quotation from Godard:

"I need a day to tell the history of a second, a year to tell the history of a minute, a lifetime to tell the history of a day."Ciao and welcome to another year of cinephilia with Adrian.

- Godard from Moments Choisis des Histoire(s) du Cinéma

Histoire(s) du Cinema (1998, Jean-luc Godard)